Before I dig into my own research, I want to summarize how we arrived at this juncture in which the scientific community cannot make basic conclusions about autism. Most are aware of the contours of this story. The short version is the following: the prevalence of autism (or autism spectrum disorders, ASD) has been going up for quite some time. While many think this is simply due to a growing awareness of the condition, some have disagreed. Somewhere along the way someone reasonably thought vaccines might have been the culprit. It sure didn’t help that the results of the study he performed were fraudulent. This is probably when all rational discussions about ASD were derailed. The theory took on a life of its own as a whole movement sprouted from its false ideas. Though subsequent research failed again and again to find any association between vaccines and ASD, it didn’t stop the community from gaining traction. Normal debating about ASD’s origins became politically fraught.

But to show you how we got here—where it seems all progress has halted—we need to go back to the beginning.

In the Beginning…

In 1933 a psychiatrist (Howard Potter) in New York City documented 6 cases of young children with similar psychopathology. He collectively called their disorder “childhood schizophrenia”, intimating that these children had early versions of the well-documented psychotic disorder in adults. However, actual schizoprehenia typically begins in early adulthood and only rarely manifests before age 13, and many of the characteristics of these patients would likely be considered autistic today. As was the fashion then, he described the children in a Freudian, psychoanalytic manner, even going so far as to suggest that their disorders were a manifestation of a pathologic interaction between parent and child.

It was in 1943 in Baltimore, Maryland that the psychiatrist Leo Kanner described 11 children of having a common syndrome which he called “autistic disturbances of affective contact” and subsequently “infantile autism.” Kanner’s main contribution was his observation—distinct from that of Potter—that the children were symptomatic even as toddlers. Also unlike Potter, he suggested that the children were innately born with the disorder, rather than being a result of poor parental relationships. In his report, he characterizes many of the features that would later be found in the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association five (DSM-V)—this manual provides the essential criteria for diagnosis of all psychiatric disorders, including ASD, and was last updated in 2013.

Interestingly, both Potter and Kanner speculated that many children who were thought to be “mental deficient” or “feebleminded” could probably be considered to have “childhood schizophrenia” or autism, already alluding to a potential underdiagnosis in the population. However, as these clinicians were the first to describe the condition, it would be expected that many children outside of their practice would also likely have an undiagnosed disorder. Cameron, another psychiatrist from the era, stated that there was a “growing acceptance of routine health examinations” with “increasing utilization of general hospitals for psychiatric treatment.” This was the context in which these clinicians found themselves observing and documenting the hitherto undocumented features of these children.

Modern epidemiology doesn’t have too long of a past, and generally, early statistics of diseases were only kept for acute conditions, like infectious epidemics. Any attempt at understanding the historical prevalence of particular diseases before this period can only be made by studying the archaeological record. Unfortunately, for our sake, psychiatric conditions don’t leave much of a record. The earliest suggestion of what the prevalence may have been comes from a study conducted prior to 1936 by someone named Hagen, who determined that so-called “child psychosis” was found in only 1 of 72,000 inhabitants of a community (unknown). As “child psychosis” would at that time also include autism, we can be fairly sure that it was not common, at least in the severest forms.

Victor Lotter is credited with carrying out the first systematic epidemiologic study of autism. Let’s halt our tour right here as it’s very revealing and can dispel much of the mythology enveloping certain favorite memes used by those inhabiting Mt. Delusion. One of the most pervasive of these is that autism simply wasn’t recognized among clinicians the way it is today. One the face of it, the logic of the statement is coherent. But let’s disentangle it. Is it that A) clinicians weren’t looking for autism, or B) the definition has changed? There may be some validity to the argument due to (A). It’s certainly plausible that some clinicians, decades ago, weren’t on the lookout for autism, particularly as inchoate articulations of the disorder were still being put forward. So if we simply add up the total cases in a location in those early years and divide by the child count in the community, it may give the wrong conclusions. But what about prevalence rates produced under controlled circumstances?

Let’s get into the details of Lotter’s study. It was conducted from 1963-64 on the entire population of children 8-10 years old in the County of Middlesex, England. The study was multistaged, with the first stage being a 22-item behavior questionnaire which was completed by teachers to screen the school population (including all special schools) . In stage 2, all children who were possible cases were screened by the author. In the final stage, 24 items were rated to select children with autism. The final prevalence rate ranged from 2.1-4.5 per 10,000, depending on specific criteria used. Even with the most expanded category of potentially affected children, the rate would be less than 10 per 10,000 (0.1%)—still quite low in comparison to modern-day rates.

So what can we make of a study like Lotter’s that uses one methodology to screen and identify all children with autism in a single community? This would completely nullify argument A (i.e., autism being unrecognized) and we would be left to see how far the goalposts (i.e., argument B) have shifted over the years.

Lotter’s definition of autism was based on Kanner’s descriptions which were compiled by Creak and consisted of 24 items divided into 5 categories:

speech

social behavior

motor peculiarities

repetitive-ritualistic behavior

"other"

Now, let’s compare Kanner’s criteria with the updated DSM-V criteria :

All of the following:

Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity

Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction

Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships

At least 2 of the following:

Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech

Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior

Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus

Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment

AND

Symptoms must be present in early development

Symptoms must cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning

Symptoms not better explained by other disorder

So has there been a great shift in the definition from Lotter to the current version of DSM? As you can see, Lotter’s criteria were more flexible than the DSM-V which now necessitates very specific social criteria. In addition,"repetitive-ritualistic" behavior is now a requirement. It’s very likely that if Lotter’s study were performed today, it would in fact be less restrictive than the DSM-V, netting a larger number of cases. Still, assessing the criteria does require a certain clinical judgement and there is potential for a clinician to be somewhat biased.

The study by Lotter should be differentiated from less stringent cross-sectional studies. For instance, a study by Treffert (Wisconsin, 1970) only accounted for cases brought to attention of the Wisconsin Department of Health and Social Services and found a prevalence of 3.1 per 10,000. Although the prevalences were similar, in these cases it could be argued that the study was “downwardly biased” in that the selection process may have underestimated the actual prevalence.

Just a couple of years later, in 1972, a study by Wing was conducted in Camberwell, England. The authors found a similar prevalence of 5 of 10,000 in children under 15. Thus far in our journey, there is no indication that autism prevalence had increased in the decade from Lotter through Treffert and Wing and studies are mostly in agreement on the specific rate.

Early Japanese Studies 日本

There was a blitz of early studies coming from Japan, the details of which I unfortunately cannot locate (likely in Japanese only). These studies all have a prevalence somewhat lower than the studies described earlier. Here are their results:

Yamazaki et al. (Hokkaido, 1971, children: 2-12 years, 2.56 per 10,000)

Nakai (Gifu, 1971, children: 15 years or younger, 1.7 per 10,000)

Haga & Miyamoto (Kyoto, 1971, children 5-14 years, 1.1 per 10,000)

Tanino (Toyama, 1971, school children, 0.9 per 10,000)

Let’s now bring our attention to a cross-sectional study from Fukushima, Japan carried out just a few years later (1978-79) by Hoshino and colleagues (1982). This two-stage survey (much like Lotter’s) gave forth a low prevalence of 2.33 per 10,000 for children under 18. Without comparing this prevalence to other studies, let’s first take a look under the hood for a deeper inspection of the data. The authors kindly provided a line-by-line readout of prevalence for all children by birth year, and the results simply make it the most important published study (available in English at least) on autism up to then (with the exception of the original Kanner paper).

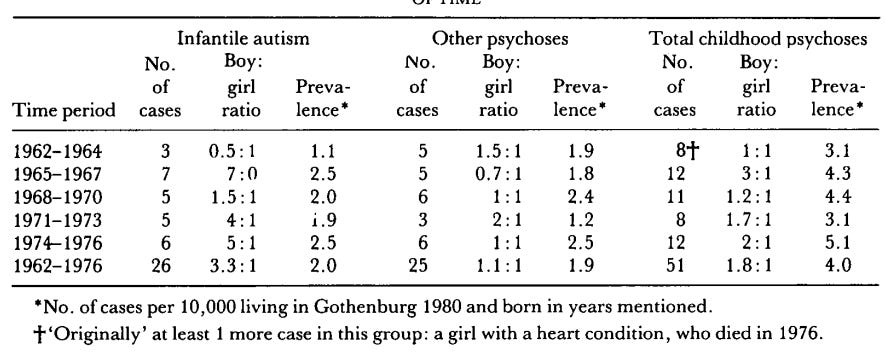

Although rates across all years remain small, on visual inspection, you can see quite a jump from those born before 1968 to those born between 1968-1974 (children born between 1975-1976 would have been only 2-3 years old and more difficult to assess and diagnose). Pre-1968 prevalence was 0.98 per 10,000 and the 1968-1974 prevalence was 4.96 per 10,000. Remember, the methodology employed to determine the status of the children was the same for each child across all birth years. Therefore, clinician awareness and moving goalposts arguments (as discussed earlier) can be safely ignored. The author explains away the findings, suggesting that older autistic children likely “lost the unique feature of young autistic children and had been overlooked in the preliminary examination.” Though children diagnosed with autism may lose the diagnosis with age (and some may even gain the diagnosis), the diagnosis is typically stable in the vast majority, as found here and here. Further, a cross-sectional, multi-stage study in Gothenburg, Sweden by Gillberg (1984) did not find a change in autism rate by birth year:

We see clearly in the Fukushima data a line in the sand for children born before and after 1967/1968. So what happened then? Let’s table this for now and come back another day.

Thus far in the timeline there’s no apparent suggestion from any researcher that the prevalence of autism may be rising. Then the 1980’s came rolling in…

Late Japanese Studies (Enter DSM-III)

The next few studies I will describe employed the newly updated DSM-III criteria that was developed in 1980 and used the term “infantile autism”. So let’s have a look at the specific criteria.

A. Onset before 30 months of age

B. Pervasive lack of responsiveness to other people (autism)

C. Gross deficits in language development

D. If speech is present, peculiar speech patterns such as immediate and delayed echolalia, metaphorical language, pronominal reversal.

E. Bizarre responses to various aspects of the environment, e.g., resistance to change, peculiar interest in or attachments to animate or inanimate objects.

F. Absence of delusions, hallucinations, loosening of associations, and incoherence as in Schizophrenia

These diagnostic criteria more or less explicitly stated, what were until then, the Kanner/Lotter criteria. In fact, in a study by Volkmar et al. (1988) of 114 patients, diagnoses of autism using clinical judgment alone were compared to diagnoses made using the DSM-III criteria. To those who are not epidemiologists, I’m going to be introducing some new terms that make a scientific comparison of the criteria possible:

The sensitivity of the DSM-III criteria was 80.8% (i.e., what percentage of children originally diagnosed by clinical judgment were also diagnosed with DSM-III criteria). This means that only 4/5 children with autism were picked up with the new criteria.

The specificity of the DSM-III criteria was 93.6% (i.e., what percentage of children diagnosed using DSM-III criteria were also diagnosed using clinical judgment). So only 1/20 children diagnosed using the new criteria would have failed to have been described as autistic using clinical judgment.

I think we can safely say that studies employing this newly developed DSM-III criteria, all else being equal, would not find higher rates.

On to the rest of the Japanese studies. Here’s a rundown of the next several studies which were all published in the 1980s, however, the birth-years of the children involved in the studies are from the 1970s. As you can see, studies range in prevalence from 13-16 per 10,000. Only 3 of the 4 studies are available in English for review.

Ishii and Takahashi (Toyota City, 1983, 16 per 10,000; birth years unknown)

Matsuishi et al. (Kurume City, 1987, 15.5 per 10,000; birth years: 1971-1979)

Tanoue et al. (southern Ibaraki, 1988, 13.8 per 10,000; birth years: 1972-1978)

Sugiyama & Abe (Nagoya, 1989, 13.0 per 10,000; birth years: 1977-1982)

Matsuishi’s study is from Kurume City, on the island of Kyushu in southern Japan, and assesses children aged 4-12 years with birth years from 1971-1979. Here the authors makes no speculations about underdiagnoses in older children as the rate among those aged 12 is similar to the youngest children. In fact they go further.

We doubt that differences in diagnostic criteria and survey methods account for these high rates, although such factors may explain the large differences between the studies done between 1966 and 1980 and the studies done since 1983. In fact, the earlier studies were carefully performed using good survey methods. Although in some studies the diagnostic criteria may have been different, the diagnostic criteria were similar in the study by Hoshino et al and in our study, and both studies were done in Japan in similar cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic regions. However our prevalence is three times that of Hoshino et al. Could the real prevalence of autism be increasing in the world? (emphasis mine)

As far as I’m aware, this is the first time a researcher has suggested that autism prevalence may simply be rising due to natural causes, as other explanations do not seem satisfactory.

Tanoue’s study comes from southern Ibaraki, near Tokyo and is of children aged 7 years with birth years 1972-1978. In comparing their study with Lotter’s, Tanoue suggests that the DSM-III criteria may be less restrictive than Lotter’s criteria (but as we discovered above, they are quite similar). As the children in Tanoue’s study are aged 7, the authors once again speculate about the challenges of diagnosing older children: ”there may be some danger of underestimation since the subjects [in Lotter’s study] were older and abnormal behavior was not so prominent.” However, as previously explained, the diagnosis is typically stable in the vast majority, as found here and here.

Sugiyama & Abe (1989) conducted their study in Nagoya at the Midori Public Health Center from 1979-1984 of children born from 1977-1982 which was on the back of a new requirement in Japan for early child checkups at 18 months of age. The authors implemented checkups at several timepoints through age 3, as 18 months was deemed too early to fully comprehend the child’s status. Children suspected of autism were followed until age 6. Sugiyama & Abe also suggested, like Hoshino and Tanoue, that studies encompassing a higher age range may find lower rates because “the defining features of autism tend to wane in children over 10 years of age.” However, in their study all children who were diagnosed with autism were followed until age 6 even though they were already diagnosed by age 3. There was no suggestion from the authors that symptoms began to wane with age. The authors also attempt another explanation: “Large populations and huge areas may reduce reliability because it becomes more difficult to observe each child directly and to follow-up all of them.” The Lotter and Wing studies may have been larger but the authors did examine all children who entered final screening. Moreover, Hoshino’s and Matsuishi’s (below) studies were even larger than Wing’s, but still found higher rates.

Unlike Hoshino who found an ever increasing prevalence across birth years in the 1960s, studies from Tanoue and Matsuishi (as you can see in the above figures) did not find any such trend in the 1970s. Therefore, based on these 9 Japanese studies, autism prevalence appears to have risen from less than 1 per 10,000 (0.01%) in the early 1960s and halted between 13-16 per 10,000 (0.13-0.16%) in the 1970s (a caveat being that each of these studies is from a different location in Japan).

Stay tuned to Part 2 of Autism Past…

Don’t forget to like and subscribe or leave comments!

Why are you publishing this on substack and not in a medical journal if you believe you've really found something in your research?